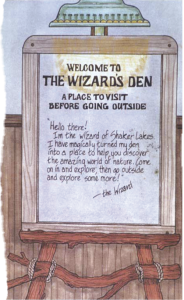

The Wizard’s Den

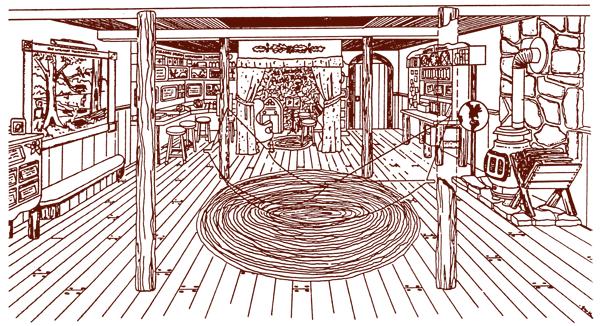

Imagine being invited into the den of a nature lover who had transformed all his furnishings into interactive stations for sharpening your senses and stimulating your curiosity about the natural world. A Chest of Drawers contains samples of different animal “clothing” found at the center, and challenges the visitors to solve riddles using their sense of touch and reveal the appropriate animal in the mirror over the chest. A large painting on one wall represents a natural scene at the center, but this painting has holes in it through which the visitors can reach inside to respond to a challenge about the life of the area. (Reaching into some holes may also trigger sound, movement, or even smells related to what’s inside, beneath, or behind what’s represented in the painting.) In another area, the nature lover has arranged several microscopes through which the visitors can look closely at natural objects, thus revealing a series of numbers, which combine to become a telephone number that can be dialed on an old-fashion phone in the den to hear a recorded message. Of course, an incorrect number is not answered (or answered in another voice that says the visitor has a wrong number), but the visitor can return to the microscopes to look closely and try again. Gradually, the visitors develop an impression of this elderly gentleman tinkering away in his den at night so they can learn about nature during the day while he is away.

Imagine being invited into the den of a nature lover who had transformed all his furnishings into interactive stations for sharpening your senses and stimulating your curiosity about the natural world. A Chest of Drawers contains samples of different animal “clothing” found at the center, and challenges the visitors to solve riddles using their sense of touch and reveal the appropriate animal in the mirror over the chest. A large painting on one wall represents a natural scene at the center, but this painting has holes in it through which the visitors can reach inside to respond to a challenge about the life of the area. (Reaching into some holes may also trigger sound, movement, or even smells related to what’s inside, beneath, or behind what’s represented in the painting.) In another area, the nature lover has arranged several microscopes through which the visitors can look closely at natural objects, thus revealing a series of numbers, which combine to become a telephone number that can be dialed on an old-fashion phone in the den to hear a recorded message. Of course, an incorrect number is not answered (or answered in another voice that says the visitor has a wrong number), but the visitor can return to the microscopes to look closely and try again. Gradually, the visitors develop an impression of this elderly gentleman tinkering away in his den at night so they can learn about nature during the day while he is away.

This was the Wizard’s Den. It was not a room for visitors to stroll through with their hands in their pockets. They had to participate, for they would not be able to exit through a special door onto the “Wizard’s Trail” unless they could respond correctly to the challenges he had set for them. His old-fashion grandfather clock next to the door posed the final challenges, but once again, the visitors could return to the “furnishings” in the room to check their responses if necessary.  The key to this design was in organizing the space around a central character, and structuring the interactive stations as a cumulative series of “challenges” for those visiting the nature center. By transforming the furnishings in his den into interactive stations, they became embedded in a narrative context, while giving them an overall direction and purpose. The result was not just a potpourri of interactives, but a carefully-crafted series of challenges designed to enrich the visitor’s experience outside. In the 80’s, many nature centers had “discovery rooms,” or the ubiquitous “touch table,” but they lacked overall cognitive engagement and meaning in relation to the place. There was “hands-on” without much “minds-on.” And when something did engage the visitors mentally, there was nothing specific to do with it outside. Tidbits and titillation substituted for meaningful and purposeful interaction. In this proposal, the Wizard’s Trail would give the visitors an immediate opportunity to practice what they had done inside. Although it was never clear why the center did not elect to pursue installing the Wizard’s Den, we suspected religious fundamentalists objected to the characterization of the old man as a “wizard.” If so, it is a good example of unrevealed agendas or points of view in the design process.

The key to this design was in organizing the space around a central character, and structuring the interactive stations as a cumulative series of “challenges” for those visiting the nature center. By transforming the furnishings in his den into interactive stations, they became embedded in a narrative context, while giving them an overall direction and purpose. The result was not just a potpourri of interactives, but a carefully-crafted series of challenges designed to enrich the visitor’s experience outside. In the 80’s, many nature centers had “discovery rooms,” or the ubiquitous “touch table,” but they lacked overall cognitive engagement and meaning in relation to the place. There was “hands-on” without much “minds-on.” And when something did engage the visitors mentally, there was nothing specific to do with it outside. Tidbits and titillation substituted for meaningful and purposeful interaction. In this proposal, the Wizard’s Trail would give the visitors an immediate opportunity to practice what they had done inside. Although it was never clear why the center did not elect to pursue installing the Wizard’s Den, we suspected religious fundamentalists objected to the characterization of the old man as a “wizard.” If so, it is a good example of unrevealed agendas or points of view in the design process.