Earth Education

Earth Education

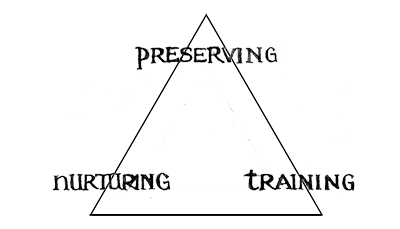

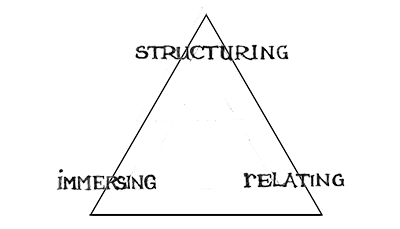

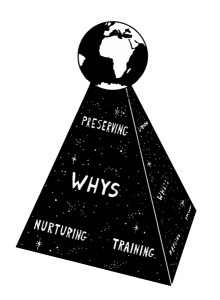

or us, Earth Education is the process of helping people of all ages live more harmoniously and joyously with the natural world. To illustrate its main components we use a structural logo, a three‑sided pyramid representing the WHYS, WHATS, and WAYS of our work, with the three points on each side of the pyramid highlighting an important outcome of that component. Together, these three triangles combine to form the supporting pyramid for the process of helping others build an understanding of, appreciation for, and harmony with the planet and its life.

or us, Earth Education is the process of helping people of all ages live more harmoniously and joyously with the natural world. To illustrate its main components we use a structural logo, a three‑sided pyramid representing the WHYS, WHATS, and WAYS of our work, with the three points on each side of the pyramid highlighting an important outcome of that component. Together, these three triangles combine to form the supporting pyramid for the process of helping others build an understanding of, appreciation for, and harmony with the planet and its life.Preserving

We believe the planet as we know it is endangered by its human passengers.

Nurturing

We believe people who have broader understandings and deeper feelings for the planet as a vessel of life are wiser and healthier and happier.

Training

We believe Earth advocates are needed to serve as environmental teachers and models, and to champion the existence of planet’s nonhuman passengers.

Understanding

We believe in developing in people a basic comprehension of the major ecological systems and communities of the planet.

Feeling

We believe in instilling in people deep and abiding emotional attachments to the planet Earth and its life.

Processing

We believe in helping people change the way they live on Earth.

Structuring

We believe in building complete programs with adventuresome, magical learning experiences that focus on specific outcomes.

Immersing

We believe in including lots of rich, firsthand contact with the natural world.

Relating

We believe in providing individuals with time to be alone in natural settings where they can reflect upon all life.

What Happened to “Environmental Education”?

Frankly, we gave up on that term. Here are some excerpts from “Environmental Education: Mission Gone Astray,” a speech Steve Van Matre presented at numerous conferences over the years to encourage leaders in our field to rethink their view about this urgent educational work:

“We think environmental education went astray, not because it lacked money or facilities or volunteers, but because it lost a clear sense of its direction and mission.

“Poke your head into most any school today and see how much real environmental education you find going on there. I don’t mean a couple of activities (inside or out) led by one or two valiant teachers, I mean focused, sequential, instructional programs as a regular, integral part of the whole curriculum. I suspect you will come away disappointed.

“Even if a few teachers do include an environmental lesson or unit, chances are good that they do not systematically address what environmental education set out in the beginning to accomplish, i.e., how life functions ecologically, what that means for people in their own lives, and what they are going to have to do to change their lifestyles in order to lessen their impact upon the planet.

“Next, stop by your average nature centre or outdoor school and see what you find there as well. The name of the place may have changed, but the staff is probably back to identifying the plants and animals, doing tombstone rubbings, testing the water, reading the weather gauges, running ropes courses, making maple syrup, espousing forest  management, etc. In other words, they’re probably offering a loose assemblage of outside curricular, recreation, and socialization activities (yes, with some sensory awareness experiences from Acclimatizing and a few environmental ‘games’ thrown in) all tied together by a schedule rather than a desire to achieve particular learning outcomes.

management, etc. In other words, they’re probably offering a loose assemblage of outside curricular, recreation, and socialization activities (yes, with some sensory awareness experiences from Acclimatizing and a few environmental ‘games’ thrown in) all tied together by a schedule rather than a desire to achieve particular learning outcomes.

“After you’ve made the rounds of our educational institutions, sit down and sift through some of the major so-called environmental education programs that were developed. You’re in for a surprise. You’ll find that several of them didn’t even deal with basic ecological understandings, i.e., concepts like energy flow or cycling. You’re asking, ‘How could someone possibly claim to have a comprehensive environmental education program and not deal directly and effectively with the fundamental basis for all life on the planet – the flow of sunlight energy and the cycling of materials?’ That’s a good question. What’s amazing is that it’s been so seldom asked.

“Other projects, as you’ll see, dealt with some of the concepts, but never attempted to clarify for their participants how their lives were connected to those concepts, nor suggested that they should examine their lifestyles in light of their new understandings. A couple of projects included a framework, even placed ecological understanding within it, but then provided only a disjointed, random accumulation of not very stimulating activities to get the job done that they had so carefully identified in their organizational structure. As a result, you often got either the activities with no good framework (the ‘Projects’), or the framework with no good activities (Stapp & Cox).

“It is also going to be pretty obvious in your examination that for some of these projects their activities were created first and their objectives formulated later. In fact, chances are good that any time you find an activity description that claims to accomplish several objectives simultaneously; you’ve found an activity that was not developed with a specific learning outcome in mind. Instead, someone probably got a group together to come up with things to do, then figured out what they hoped their products were going to achieve afterwards.

“You should also check out how they placed such activities in various subject areas while you’re at it. It probably went something like this – imagine for a moment people sitting around a table commenting upon an activity like making maple syrup: ‘Well, let’s see, they figured out the number of buckets of sap it takes to make a jar of syrup didn’t they, so it’s a math activity.’ ‘Ok. And they listened to the sap gurgling beneath the bark, that means it’s a science activity.’ ‘Don’t forget when we told them how the pioneers did it. That’s social studies.’ ‘True, and they had to write a report on it when they got back, so it fits in language arts as well.’ Want to guess how someone would justify this as an environmental education activity to begin with? ‘Well, we discussed multiple forest roles with the kids while they watched the sap boiling down.’ R-i-g-h-t….

“You should also check out how they placed such activities in various subject areas while you’re at it. It probably went something like this – imagine for a moment people sitting around a table commenting upon an activity like making maple syrup: ‘Well, let’s see, they figured out the number of buckets of sap it takes to make a jar of syrup didn’t they, so it’s a math activity.’ ‘Ok. And they listened to the sap gurgling beneath the bark, that means it’s a science activity.’ ‘Don’t forget when we told them how the pioneers did it. That’s social studies.’ ‘True, and they had to write a report on it when they got back, so it fits in language arts as well.’ Want to guess how someone would justify this as an environmental education activity to begin with? ‘Well, we discussed multiple forest roles with the kids while they watched the sap boiling down.’ R-i-g-h-t….

“Perhaps the most damaging development though was the assertion you’ll find in many of these ‘projects’ that leaders should use the materials in any way they like. In other words, people should just pick and choose whatever caught their fancy, or whatever happened to fit with what they were doing at the time. Hardly anyone said, ‘Hey folks, if you’re going to be serious about an educational response to our environmental problems, then it won’t work just to sprinkle a couple of activities around like so much spice. You’re going to have to put together some focused, sequential programs to get the job done. Just bagging up a batch of activities and calling them a program is like tape recording a batch of sounds and calling them a symphony….’

“Perhaps the most damaging development though was the assertion you’ll find in many of these ‘projects’ that leaders should use the materials in any way they like. In other words, people should just pick and choose whatever caught their fancy, or whatever happened to fit with what they were doing at the time. Hardly anyone said, ‘Hey folks, if you’re going to be serious about an educational response to our environmental problems, then it won’t work just to sprinkle a couple of activities around like so much spice. You’re going to have to put together some focused, sequential programs to get the job done. Just bagging up a batch of activities and calling them a program is like tape recording a batch of sounds and calling them a symphony….’

“In the end, I think we’re going to have to face up to it: a lot of otherwise well-meaning people have been misled about the nature and purpose of environmental education. And as a result, it’s become everything to everyone, or not much of anything to anyone. One of my favorite definitions that appeared in the early days was the one that goes ‘environmental education is education that is in, about, or for the environment.’ Gosh, no wonder people got confused. Under that definition, what isn’t environmental education? And if any of these perplexed folks went off to a national conference looking for some answers, they would probably find everything from orienteering to acid rain on the program. Or in other words, everything from outdoor recreation to environmental studies. It’s no wonder that the idea of developing focused, comprehensive education programs seemed to get lost in all of this potpourri of goals and offerings.

“Here’s the bottom line: we don’t need more collections of supplemental curriculum activities. They won’t get the job done. We need specific, comprehensive units of instruction for specific settings and situations. Let’s develop these focused programs and then go out there and sell them to the boards of education, youth groups, nature centres, adult organizations, park districts, etc. Anything short of this will only further the educational hypocrisy that already exists.

“Please don’t misunderstand: we don’t think our way is the only way to get there, but we do think knowing where we are going and paying attention to how people learn is a big advantage. Nor do we think that everyone should be doing earth education all of the time, but we do think its influence on everything else is inescapable. Finally, we don’t mean to belittle everything that’s been done in the past, but we do think that many of those in pursuit of EE have lost their way.

“Again, I apologize for how negative all this sounds, but I think it was Einstein who said, ‘If you don’t know there’s a problem, you don’t have anything to think about.’ Believe me, there’s a problem. Won’t you join us in thinking about it?”

Environmental Education vs. Earth Education

Environmental Education

(Tendencies)

- supplemental and random

- classroom based

- issues oriented

- focuses mainly on developing secondary concepts and conducting environmental studies and projects

- activity based

- claims to teach how to think, not what to think

- relies heavily upon conducting group discussions to achieve its instructional objectives

- integrates the inputs (messages) and consolidates the applications (projects)

- infused with “cornucopian” management messages and views

- accepts a wide range of definitions and intentions

Earth Education

(Aims)

- integral and programmatic

- natural world based

- lifestyle oriented

- focuses largely on developing “ecological feeling” based on a combination of mental and physical engagement with the natural world

- outcome based

- claims to instill values and change habits

- relies heavily upon conducting participatory educational adventures to achieve its instructional objectives

- consolidates the inputs (messages) and integrates the applications (projects)

- infused with the original ideals of deep ecology

- rejects becoming everything to everyone

What about Education for “Sustainable Development”?

Steve Van Matre addressed this question in the institute’s 2000 Annual Report:

“Ah, sustainability…

It has become the term of the day in environmental circles, but perhaps that’s because no one knows what it means. People feel good talking about ‘sustainability’ simply because they don’t have to draw a target and demonstrate they can hit it. In other words, everyone can have a piece of this cake and jump on it too! No tough personal choices. No down-sizing of consumption. No specificity that might scare anyone (or, god forbid, lead anyone to conclude that somebody might be really serious about all this). You just add the word sustainability to everything you’ve been doing or want to do, then smile, smile, smile. (It reminds one of environmental education, doesn’t it?)

It has become the term of the day in environmental circles, but perhaps that’s because no one knows what it means. People feel good talking about ‘sustainability’ simply because they don’t have to draw a target and demonstrate they can hit it. In other words, everyone can have a piece of this cake and jump on it too! No tough personal choices. No down-sizing of consumption. No specificity that might scare anyone (or, god forbid, lead anyone to conclude that somebody might be really serious about all this). You just add the word sustainability to everything you’ve been doing or want to do, then smile, smile, smile. (It reminds one of environmental education, doesn’t it?)

“Sustainability became a nice feel-good word in the 90’s, a verbal massage for our environmental woes. It sounded so soothing and hopeful, and everyone was weary of all this environmental bad news. People yearned to change channels and sustainability gave them permission. After all, they didn’t have to do anything personally; our governments and businesses had commissions and committees working on it.

“After one of my Sunship Earth speeches on the plight of the earth, a woman came up to me and asked how I had come to their conference. When I replied that I had flown in, she seemed visibly pleased, as if vindicated somehow that the messenger warning of corporate excess and influence had used one of their products himself (oil) in coming there to deliver his message. Of course, attacking the messenger is not a new tactic for those who don’t want to deal with the message delivered, but I was still surprised by her vehemence. Do you suppose she would not have denounced slavery two hundred years ago because she wore cotton? It’s not the use of oil that we oppose, but how it is obtained and processed (and wasted), and the lack of government leadership for more efficient use and less impacting alternatives. Nonetheless, I often wonder if my use of oil is justified in the larger scheme of things, and can only hope my educational message, and the energy I put into delivering it, will offset such consumption, but I admit it’s a close call.

“Most environmental scientists I know estimate that we have about fifty years left to sort out our relationship with this planet, a small window of opportunity before irreversible ecological catastrophe occurs here. For many of our modern leaders sustainability must seem like the perfect incantation for warding off such evil because it lends itself to the technological fix we invariably seek. It offers a way of putting off tough ‘big picture’ choices in the here and now in favor of ‘little picture’ efforts which no one fears will substantially alter our presumed economic success. Our planetary exploitation (of both natural and human resources) can continue unabated. All we have to do is manage its systems better. It’s a dream come true for those with a vested interest in the status quo. Sustainability deflects serious change in favor of minor ‘feel good’ efforts. The image of Nero fiddling while Rome burned is probably apocryphal at best, but that’s exactly what the term sustainability allows our present leaders to do. By the end of this century sustainability may be remembered as the pleasant sounding fiddle of the environmental movement.

“The corporate folks support it because it gives them a way of putting an environmental face on their work without making fundamental changes in the way they do business. (It’s their equivalent of picking up litter.) The politicians salivate over it because no one can get on their case for not doing it since no one really knows what ‘it’ is. (So they just insert the word here and there as evidence that they are among the savvy good guys.) And the bureaucrats adore it because they’re accustomed to working on things that are ill-defined and often un-measurable anyway. (They can just nibble away at the problems while producing mounds of self-satisfying paperwork.)

“Finally, the educational gasbags love sustainability because they never have to do it, just talk about it (or better yet, get their students to write reports about it, which they can comb through looking for material for their own papers). It’s inflated the limp and declining bags beautifully on the environmental education scene. In fact, many of those folks, especially the ones who could never get that job done either but have run out of gullible sources to tap for funding, have now added sustainability to their business cards and become instant consultants again. Gosh, you have to give them credit; they’re good at staying afloat.

“Frankly, the idea of sustainability appears to foster little passion in many of those who espouse it. Even though there are some valiant souls out there trying desperately to make it mean something, overall, it seems to be primarily a bureaucratic response to our environmental problems. Certainly, it has brought the idea of general environmental limits, however illusive, into some political and corporate discourse (if not the actual decision-making), but most of those folks don’t appear to be driven by a deep and abiding love for the biological richness of the planet. They march to a different drum. It’s Buy, Buy, Buy… not Why? Why? Why?

“I am often asked if we shouldn’t work with the corporations to help them become more environmentally aware. Of course, we should, but we shouldn’t fool ourselves by using that as a rationale for taking their PR money. We can work with them without their sponsorships. And we can encourage them to give environmental support to blind trusts which do not pass along their corporate logos. However, we should not forget that they are well aware of the old adage that it’s better to have someone in your tent pissing out than the other way around. (You have to picture that one.)

“Just because some corporate leaders invite us to sit at their table doesn’t mean they will make any elemental reform in how they do business. I know, I know. In light of all those corporations who have honestly labored to be more environmentally friendly, this sounds like I believe no good deed should go unpunished. On the contrary, I believe we should applaud those corporations for their steps, even when they are baby steps. I just don’t believe we should allow ourselves to become part of their promotional efforts in the process. Paying lip service to environmental concerns, publishing ‘sustainability’ plans, or even applying an environmental band-aid here and there, is not the same as addressing the real questions of human impact on this planet. I suspect large numbers of people now think they have done their environmental thing by these attempts to manage the systems instead of themselves.

“If the incredibly rich and varied life of this planet is to survive as we know it, then the kind of sacrifice required of us this century will be most likely motivated by passion or fear, and we don’t seem to have enough of either at the moment. Should an alien species of life from another solar system threaten the survival of the awesome panoply of life here, I suspect we would set aside our social differences in order to combat it. But what if that alien species turns out to be us, and we don’t see it? Or we are too busy dealing with our social differences? Sustainability may unwittingly encourage such denial, avoidance and blindness.

“Have you seen how some of our leaders define sustainability? How about this one from the Sustainable Development Commission in the UK: ‘Sustainable development (is) development which meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.’ Huh? Whose needs are we talking about here? The consumer-driven, advertising-besotted, physically-northern and culturally-western masses? Are those the lifestyles we’re trying to sustain in the future? Not surprisingly, very few of our leaders want to talk much about those choices. And what about all the other creatures that share the planet with us? Will our ‘sustainability’ promote theirs?

“And what ‘development’ is sustainable, please? Is that intended to be an oxymoron or what? I thought it was the development part that’s gotten us into so much trouble here. How about sustainable undevelopment instead? I suspect that’s what we will really need to sustain if we are to save the planet as we know it.

“In an issue of the magazine, Green At Work, a columnist defined sustainability as, ‘a process of understanding and responding to stakeholder interests that are strategically important to the organization.’ Hmm… I thought we were talking about sustaining the planet, not the organization. Today, we have an economic engine fuelled by ever-increasing consumption in an ecological vehicle with no exhaust. That’s not sustainability; that’s madness. And the corporate world is responding by turning sustainability into a method for dealing with stakeholder interests. Ouch!

“Granted, the term ‘sustainability’ has given people the feeling that this is not just something discussed by academics, and it’s a far more generic and palatable term than environmental education. (In fact, its greatest service may be in pushing the flawed environmental education movement aside.) On the other hand, the speed with which the academics claimed it as a part of their portfolios should have alerted us to what was coming. Today, more and more of academia can be divided into two broad categories: those who produce and those who suck. Not surprisingly, the corporate world has attempted to buy up most of the producers, either directly or indirectly, and they squirt just enough monetary sustenance into the mouths of the suckers now to keep them content. (Conferences of the North American Association for Environmental Education, for example, are routinely sponsored by oil, chemical, timber and electrical companies.) So sustainability seems to have been destined from the start to become a funding tool as much as anything else in that milieu. When George the First (US not UK) went to Rio, sustainability came back. It’s a nice soporific for those worried about unfettered globalization.

“It’s also true that sustainability offers a great way of overcoming differences among people (temporarily, I suspect, because it has no measurable outcomes, only a vague intent for the distant future to which everyone can aspire), and thus has become the darling of social ecologists. It may even move us forward a bit environmentally, but in the end, I fear it’s mostly a superficial response that will only serve to make us more indifferent and jaded. I am sure the relatively small number of human beings who now control much of Earth’s natural resources will feel it means sustaining the lifestyle to which they’ve become accustomed. That scares the stuffing out of me.

“In short, if people knew what sustainability really meant, they wouldn’t like the term. We need to ask people to make more changes in their lives. Not just little ones, but big ones. To use less energy and consume less material. To produce less children and adopt more neighbors. To avoid fast food and designer clothing. To heal the land and restore its richness. (Earth educators, please take note.) As people often ask after one of my speeches: ‘Do you mean we have to go back?’ Good god, yes. The only question is how far, how fast and what do we take with us? That’s what we should be dealing with today… while we have time.

“Okay, so we started over in the institute….

“Earth education is the process of helping people live more harmoniously and joyously with the natural world. And we divided the overall structure of that process into three parts: the Whys, the Whats, and the Ways. They combine to form the supporting pyramid for the process of helping others build an understanding of, appreciation for, and harmony with the earth and its life.”

What Do We Mean by a “Program”?

“Programs. Like environmental education and sustainability, this is another term in the field that we have been questioning for a long time. It’s a terribly abused word in education. Typically, an outdoor centre will give a new staff member (or worse, a temporary intern) a few days to look through a jumbled collection of ‘resources’ and put together a field trip for the local schools and youth groups they serve. In other cases, this newcomer won’t even bother to read the materials, but will just tag along with another staff member and watch what’s done, then let a personal version of the activity ‘evolve’ over time in the doing. Really. This is what passes for a program at sites and centres around the world. Naturally, depending upon the leader, some of the results are better than others. Many are abysmal.

“All of this is usually justified with the mantra, ‘The kids and their teachers like what we do here.’ And no one points out that they got out of school to do it. Just think what you would have to do to those learners and their leaders for them to say, ‘Don’t ever take us out of school to go to places like that again!’ In our work, we believe a genuine instructional program should be a carefully-crafted series of educational experiences that are focused, sequential, cumulative, and designed with specific outcomes in mind. Those outcomes are neither environmental categories (like Insects) nor environmental bromides (like ‘Give a Hoot, Don’t Pollute’). Instead, they go to the very heart of what we are trying to accomplish in an educational response to our lack of ecological understanding, natural appreciation, and personal harmony regarding this marvelous planet and its other life.”

Characteristics of an Earth Education Program

An earth education program:

- Hooks and pulls the learners in with magical experiences that promise discovery and adventure (the hooker).

- Proceeds in an organized way to a definite outcome that the learners can identify beforehand and rewards them when they reach it (the organizer).

- Focuses on building good feelings for the earth and its life through lots of rich, firsthand contact (the immerser).

- Emphasizes major ecological understandings (at least four must be included: energy flow, cycling, interrelationships, and change).

- Gets the descriptions of natural processes and places into the concrete through tasks that are both “hands‑on” and “minds‑on.”

Uses good learning techniques in building focused, sequential, cumulative experiences that start where the learners are mentally and end with lots of reinforcement for their new understandings.

Uses good learning techniques in building focused, sequential, cumulative experiences that start where the learners are mentally and end with lots of reinforcement for their new understandings.- Avoids the labeling and quizzing approach in favor of the full participation that comes with more sharing and doing.

- Provides immediate application of its messages in the natural world and later in the human community.

- Pays attention to the details in every aspect of the learning situation.

- Transfers the learning by completing the action back at school and home in specific lifestyle tasks designed for personal behavioral change.

Model Earth Education Programs

The institute has ten model programs in its master plan. Here is a summary of the current developmental status of each:

Earthborn — 0-3 — a series of earth-bonding experiences – idea stage

Earthlings — 4-5 — structured activities for building a sense of wonder, place and care — initial piloting

Nature’s Family — 6-7 — special events organized around the characteristics and needs of life — in design

Lost Treasures — 8-9 — classroom activities and field excursions focusing on natural communities — final piloting

Sunship Earth — 10-11 — a 5 day adventure in discovering seven key ecological concepts — published

Earthkeepers — 10-11 — a 2 ½ day experience for preparing to use less energy and materials — published

Rangers of the Earth — 10-11 — a 1 day exploration that initiates year-long learning and practice — published

Sunship III — 13-14 — a 2 ½ day exercise emphasizing the choices to be made about the human impact upon our home in space — published

Earthways — 16-19 — a small group working together to develop personal responsibility while getting to know the natural riches of their planet — in design

Earthbound — 20 — weekend experiences for building a more harmonious and joyous relationship with the natural world — initial piloting

(All of the institute’s programs help the participants form good enviromental habits.)